What Buddhism Taught Me About Neuroscience

Published:

Have you ever felt that sharp sting when reality doesn’t match what you hoped for?

When the job, the grade, or even a conversation turns out differently than you imagined?

Turns out both Buddhism and modern neuroscience, though separated by centuries and cultures, converge on this truth about this mismatch:

Much of human life unfolds in the tension between expectation and reality, also called, “suffering”.

“I want things to meet my expectations”

Suffering comes from this thought.

In the Buddhist sense this is called attachment (or clinging). It is a fundamental cause of suffering. In the Second Noble Truth, the Buddha taught that suffering (duḥkha) is “due to attachment”, where attachment translates the Sanskrit/Pāli term tṛṣṇā/taṇhā, meaning thirst, craving, or clinging (Tapas Kumar Aich, Buddha Philosophy and Western Psychology) .

We desperately want reality to align with our internal ideals of how things should be.

This rigid desire (similar to the omnipotent narcissism humans develop in infantile stage) for a perfect alignment between our expectations and reality inevitably leads to disappointment and distress when the world doesn’t comply. As one modern summary of Buddhist psychology puts it: “suffering arises from ‘attachments’ or rigid clinging to ideas that fail to match reality” (Tapas Kumar Aich).

In other words, when we cling to expectations that life or people must be a certain way, we create a dangerous gap between what is and what we want, and that gap is where suffering emerges as frustration, dissatisfaction, or grief.

Your Brain is a Prediction Model

However, as we know, humans aren’t only sentient beings in the Buddhist lens; we’re also intricate biological systems whose parts serve specific, explainable functions. In fact, modern neuroscience provides a strikingly parallel explanation for why mismatched expectations cause suffering.

According to the predictive coding theory, the brain is not a passive recorder of reality but an active prediction engine.

Our brains are constantly trying to predict what will happen next by using internal models built from past experience (Brown & Brune, The role of prediction in social neuroscience ) . We carry an unconscious mental expectation for almost everything, from what we’ll see or hear in the next moment to how others will behave or how events should unfold.

Let’s look at an example together. This is something that likely has happened to a lot of people.

Let’s say you text a close friend, “Can we talk?” and you expect a quick, reassuring reply because that’s what usually happens. Instead, hours pass in silence. Even though nothing concrete has happened, you feel a tightness in your chest and your mind starts spiraling……Did I do something wrong? Are they upset? Is something bad going on?

The discomfort, or suffering, comes from the world not unfolding the way your brain assumed it would.

In this situation, what happened under the hood is: Your brain used prior interactions to predict an outcome (a timely response). The silence produces a prediction error, which is a mismatch between the predicted signal and the actual input.

That error flags “uncertainty” and forces your brain to revise its model: maybe your friend is busy, maybe the relationship is changing, maybe there’s a threat.

While updating, the brain often allocates more attention to scanning for explanations and prepares the body to respond, which can show up as anxiety, rumination, and heightened vigilance until the model stabilizes again.

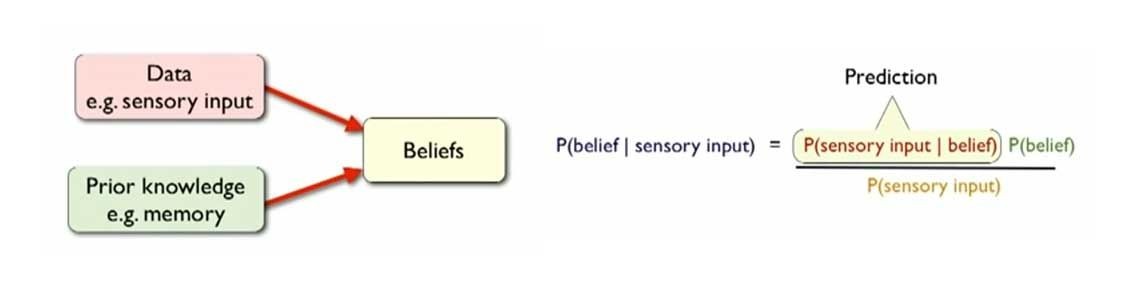

This framework, known as the Bayesian brain theory, suggests that perception, decision-making, and even action are driven by probabilistic inference:

The brain combines 1. prior beliefs with 2. incoming sensory evidence to form the most likely explanation of the world.

“We don’t passively receive reality, we actively construct it through a cycle of prediction and error correction.”

Specifically, the brain continuously compares its predictions to the actual sensory input from the world. When reality matches our internal model, things feel “right” and we proceed smoothly. But when reality violates our expectations, the brain generates a prediction error, basically an internal signal that something unexpected or “off” has occurred.

Neuroscientists use this term “prediction error” to describe the difference between what we expected and what actually happened. This error signal forces the brain to update its model of the world. If the mismatch is small, the brain may ignore it or chalk it up to noise. However, if the mismatch is large or important, higher-level brain regions are alerted that the model was wrong, and we immediately notice the discrepancy.

In psychological terms, an unmet expectation creates cognitive dissonance (maps to suffering in the Buddhist sense yet again), “the uncomfortable gap between what we expected and what actually occurred”

In those moments, we viscerally feel that

Something is not right.

Active Inference vs. Perceptual Inference

Within the framework of the predictive/Bayesian brain, two complementary strategies emerge for dealing with mismatches between our expectations and reality: perceptual inference and active inference.

Perceptual inference is about updating our beliefs when the world surprises us. For example, if you expect silence but hear a bird chirp, your brain revises its internal model: there’s a bird nearby.

Active inference is about acting to reduce prediction error. If you expect warmth but feel cold, you might put on a sweater. Instead of changing your model of reality, you change reality itself to better match your prediction.

These two modes—updating the mind to fit the world, or changing the world to fit the mind—mirror the Buddhist practice of observing thoughts (mindfulness) versus taking action (skillful means).

Mindfulness is the deliberate observation and acceptance of reality “as it is,” even when it contradicts our mental models. Meditation trains practitioners to notice sensations, thoughts, and feelings without immediately trying to change them—which in predictive modeling terms means loosening the grip of priors and allowing direct experience.

Active inference, on the other hand, is similar to the Buddhist principle of skillful action (upāya).

Upāya is the action of taking compassionate steps to alleviate suffering, whether through ethical conduct, generosity, or care for the body. In Buddhist psychology, wisdom arises from knowing when to accept and when to act, a balance the brain itself constantly negotiates through its predictive machinery.

The Meaning of Life

“Okay… so there is a connection between neuroscience and Buddhism. What now?”

Well, great question.

From the perspective of both Buddhist teachings, and their links to neuroscience theories, I’ve actually come to the following argument:

The meaning of life is not found in eliminating prediction errors or forcing the world to bend to our expectations.

Some of us spend our entire lives chasing an idealized “happy life”, trying to suffer as little as possible, stay hypervigilant forever to either avoid that dangerous gap between expectations and reality, or try to fill it with accolades, thrill-seeking behaviors, or an unnecessary amount of wealth.

However, such total control is impossible, both in the Buddhist and scientific sense, and the pursuit of it only deepens our frustration.

Prediction errors are a core feature of the brain: they help update our internal model so perception and behavior stay aligned with reality, especially in what we can influence. But we can never predict the world perfectly; uncertainty is built in, thus this gap (suffering) will always exist.

From a Buddhist lens, suffering comes from clinging to expectations and resisting what is. If the “self” isn’t fixed, then “my expectations” and the “gap” they create aren’t solid problems to solve, but mental constructions.

Chasing certainty becomes chasing an illusion, and peace comes from seeing that clearly and loosening the grip.

The older I am, the more I find meaning emerging in how we respond, in learning to move gracefully through “suffering”: uncertainty, and sometimes grief and disappointments. All of these are a part of life. The unavoidable gaps that we will never be able to fill.

Buddhism, at its core, teaches that true freedom arises when we loosen our attachment.

So, I see both Buddhism and Neuroscience as ways to help people cultivate more meaningful, and thus more fulfilling lives.

While neuroscience provides the mechanism on the how and why: how the brain constructs and revises its models of reality and why we should give mindfulness a try; Buddhism offers the daily practice through meditation and yoga, these are exercises that help you cultivate awareness, compassion, and acceptance in the midst of flux.

If you’ve made it this far, thank you for joining me on this journey. I hope you’ve taken something away from it.

Author’s Note

Ever since I was a kid, I’ve found myself asking big questions about the meaning of life. Over time, exploring both religion and science helped me get a clearer picture of what life could mean—definitely not saying that there is a single right answer. Also, people’s understanding of life changes over time. But my takeaway from learning Buddhism is that goals can inspire us, yet becoming obsessed with what we haven’t yet achieved can turn toxic.

To me, meaning doesn’t only lie in achieving goals, it also lies in understanding the patterns of the mind, embracing the inevitability of change, and finding peace in that fragile space between expectation and reality.

月有阴晴圆缺

And that’s the true beauty of life.

Nicole Hao, New York, 2025